My Apologies for not getting these stories out sooner! I had an incredibly busy October and time got away from me to write. With that, enjoy the remaining glacier blog posts!

September Glacier Trip

September’s glacier trip found me on the ice with a team of six volunteers, Colorado University, Boulder geology professor Robert Anderson (the other institution involved with the glacier study), and of course, Yosemite National Park geologist Greg Stock. The goals this month: Record the position of glacier stakes since August and begin the removal of equipment from the area, as the study’s end is the first week of October. In addition, stream and temperature gauge data was downloaded, as part of a water discharge study, and then the equipment was removed, per Leave No Trace wilderness principles. The biggest piece of equipment removed was the meteorological station (MET station for short), which has recorded weather data in the region since the early days of the glacier study nearly 4 years ago. After the final data was collected onto Greg’s laptop, the MET station was dismantled, divided up amongst the volunteers, carried down to base camp and eventually out of the back-country.

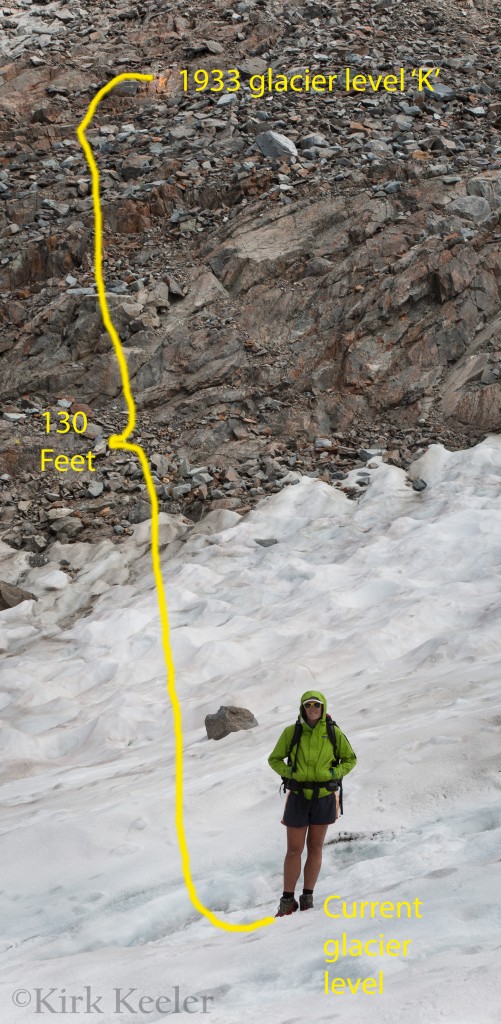

Cooler September temperatures slowed glacial ablation enough to hold six of seven stakes in their positions, making measurements far easier than August. Still, we had to drill the holes deeper to ensure they would be intact to measure on our final October trip. While on the Lyell glacier, I wanted to make sure to photograph a marker on a rock face – a ‘K’ – which marked where the glacier’s surface was during a 1933 survey . I was very interested in knowing the elevation difference between the ‘K’ and the current glacier surface, now below it. Professor Anderson loaned me his lazer rangefinding device to get this distance. I walked over to a spot (see below photo), found a piece of exposed ice at the end of the glacier, got down at ice level, and shot the lazer right at the ‘K’. 40 vertical meters came back (approx. 130 feet).

So, between 1933 and 2012, the Lyell glacier lost around 130 vertical feet of ice from my position. To put this in perspective, imagine you were walking on the Lyell glacier in 1933. You would be 130 feet above my head, more or less, a massive ice sheet between you and me! It’s not there anymore. In 79 years, all that ice has melted away. With 2012 California and national temperatures breaking records for more consecutive highs each year, these conditions seem to point towards more melting.

The most important analysis, however, will be the data collected from the stakes off both the Lyell and Maclure glaciers. Reading my first blog post from this project, you will remember that in order for a glacier to be considered such, it needs to have enough mass to move. If it’s not moving, it would be considered more of an ice field than a glacier.

A conversation with Greg revealed even more interesting glacier facts. The Sierra glaciers have oscillated in behavior throughout the mountain range’s lifetime. Glaciers have grown and retreated several times. Greg even mentioned that at one point, glaciers were completely absent from the range. He emphasized that these oscillations have had thousands of years of regularity between them. By contrast, this last retreat to present time took only 150 years of time – extremely out of the norm and notably beginning the same time as the Industrial Revolution (roughly 1850); the time when burning fossil fuels and releasing C02 into the atmosphere began in earnest by humans. “The last 150 years”, Greg points out, “is very much out of [geological] regularity of past Sierra glacial retreats.”

Having finished this trip’s work on the Lyell, the team hiked to the Maclure region the next day for measurements and some clean-up of old stakes, left behind from previous glacier studies, dating as far back as the 1970’s. Similar stake conditions to the Lyell made for easy lazer rangefinder measuring and re-drilling of the stake holes. This day found me walking alongside professor Robert (Bob) Anderson, using an ice auger to make the stake holes deeper and holding a prism above the stakes for Greg to get distance measurements from his lazer rangefinding station at the base of the glacier.

Bob was a pleasure to work with and listen to! He has previous experience working with glaciers at Glacier National Park and told the group stories about being underneath glaciers, setting up monitoring equipment. He also worked on Colorado glaciers and had just returned from Alaska studying glaciers there before our trip. He was grateful for my camera knowledge – especially when I turned on the Highlight indicator in his Nikon camera. In Bob’s spare time, he enjoys photography and still employs his 4X5 medium format film camera to capture images.

Speaking of being underneath glaciers…After the team was finished with our Maclure Glacier work, Greg took us to one of the Maclure’s amazing wonders – its ice caves! We entered two at the toe of the glacier and a whole different world revealed itself! We were on newly scraped rock, covered with glacial flour, while the bottom of the glacier was the roof of the cave. This world stayed at a constant temperature around 32 degrees Fahrenheit, allowing for all sorts of ice forms to be present. The pictures below show a few of the things seen there. Going into the Maclure ice caves was not only a highlight of this trip, but a highlight of all my trips to the glaciers this year!

One last note: Weather on this trip, while cooler and with more wind, was much more pleasant than the August trip (Read my blog post on the August Glacier Trip to see what happened then). Clouds formed, but rain never fell. Also, Shauna loaned me her two-person tent, which when pitched correctly, had no problems with the stiff winds we had and allowed me lots of room to keep my gear dry in case of rain.

With each glacier trip, I have gained more respect for Greg and Bob and the information that they are retrieving for their study. I believe this knowledge will have a significant impact not only on the health of Yosemite’s remaining glaciers, but bring additional and unique awareness to the larger impacts of human-caused climate change. Stay tuned for part two of this blog on October’s final glacier trip and for future posts when Greg’s final report is done! The next post will also have initial findings from the survey – the first public writing of the results from your’s truly. Historic!!